Just south of Newcastle lies a lagoon created from the moon’s tears. According to the Dreamtime story – When the Moon Cried, there was a point during the Creation era when the moon felt his people cared more for the sun. He disappeared and began crying, with his tears forming Belmont Lagoon. Much to his surprise, everyone rejoiced when he eventually returned, because the lagoon was a new life force with plants, fish and animals.

This is an abridged telling of the story, but it’s indicative of the richness of Aboriginal history and the sacred bond between people and country. All around Newcastle, there are significant cultural sites just like Belmont Lagoon, and one organisation is helping to create a tangible way for Aboriginal people to reconnect with and protect their country, even if they live in an urban area.

That organisation is Firesticks Alliance and it was established to revive the practice of cultural burning, which refers to the custom of using fire to manage country. These burns are often ceremonial in nature and have been practised for thousands of years, but that’s not the only way they differ from modern types of controlled burns. While many controlled burns focus on mitigating the risk of bushfires, cultural burning is also concerned with healing country.

“If you apply fire using cultural burning methods, you can get a cooler fire that trickles like water through the landscape,” explains Jessica Wegener, a director of Firesticks Alliance. “There are many native plants that seed and rejuvenate better with fire and without managed burning, monocultures can begin to develop.”

Jessica co-founded Firesticks Alliance after realising that knowledge from elders, including those in her family, was at risk of being lost if it wasn’t practised. She now works with other organisations including local councils, Local Aboriginal Land Councils, fire agencies and community groups to revive cultural burning and conduct scientific monitoring. She explains that the benefit of cooler fire is that it doesn’t wipe out an entire ecosystem, but rather slowly burns off grasses, bark and fallen leaves and feeds the soil with nutrients from the ash. This gives animals time to retreat, gently halts invasive species and removes leaf litter clogging the landscape.

These are just some of the ecological benefits of cultural burning. However, the personal and spiritual aspects may be the most profound when it comes to engaging the community in tackling climate change.

“Within traditional cultural practices, everyone was really connected and there was a responsibility back to the landscape within all Aboriginal people,” Jessica says. “It’s really important to bring back that sense of connection and responsibility to our local areas and I think moving into the future, this is a huge thing that’s missing in relation to climate change.”

The first pilot cultural learning program created by Firesticks Alliance has begun in the Hunter, which will transfer Aboriginal ecological knowledge to more than twenty participants over three years. It’s called the Cultural Fire Burning Program and is being delivered in partnership with Hunter Local Land Services and Tocal College. By the program’s end in 2022, participants will have developed seasonal cultural calendars, burn plans and experience in maintaining landscapes, and this knowledge can then be transferred throughout the community.

One of the program’s participants is Kentan Proctor, who is learning to read country and plan cultural burns, so he knows when fire is required and why. “Different students from different areas are in the program and we can work together and help burn on each other’s land,” he says. “It brings everyone together to continue the traditions.” Kentan lives and works on Awabakal country and is a part of the Worimi and Biripi nation.

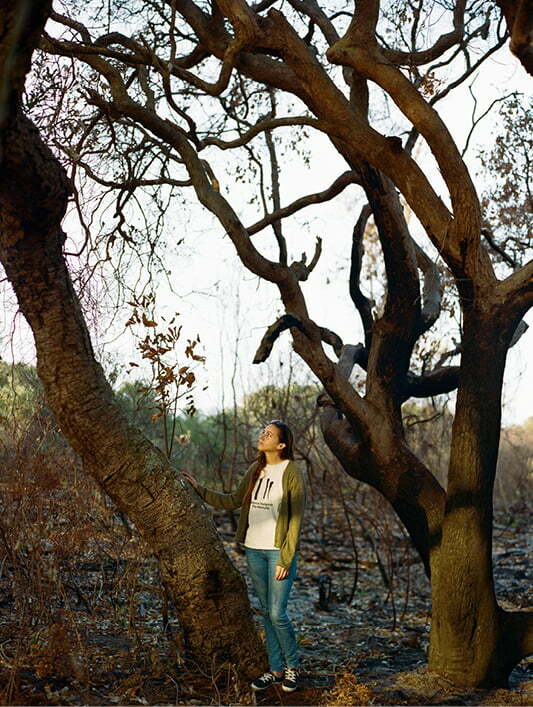

At Blacksmiths Beach, just near Belmont Lagoon, the program’s third cultural burn took place in August together with Bahtabah Local Aboriginal Land Council (BLALC), whose country the site is located on. Kentan’s mother Aunty Carol Proctor is CEO of BLALC and says this was the first cultural burn on this country in her living memory. It brought together more than eighty people from all over the community and has helped a lot of plants to begin sprouting. But despite these positive impacts, the country is still considered sick and will require further burns and activities under the program.

It is discoveries like this that knit the community closer to the land – and that’s exactly what Jessica hopes to achieve.

When we visited the site with Kentan, Aunty Carol and Jessica to see how the country was healing after the burn, Kentan performed a smoking ceremony where he told the lore of When the Moon Cried to remind us of the importance of restoring the land’s health.

“The landscape has an energy within itself,” Jessica says as she explains the significance of this particular smoking ceremony. “Sometimes the cultural aspects of a smoking ceremony could be that you don’t want to take on the effects of a sick landscape, so the intention was to remove any bad energy.”

The Blacksmiths burn also revealed a midden, which is a significant place where waste was collected to prevent littering of country. The presence of oyster shells and cockleshells in the midden offers insight into the history of the land, as they’re no longer seen in the area and paint a picture of the landscape prior to colonisation.

It is discoveries like this that knit the community closer to the land – and that’s exactly what Jessica hopes to achieve. Cultural burns promote a sense of social inclusion and wellbeing, while also giving the community a hands-on way to connect with their local area, rather than experiencing it passively.

“When knowledge starts trickling out into the wider community, it ends up being a shared responsibility between the Aboriginal community and the society we live in now. If you ask a lot of the elders, they want Aboriginal people to start sharing their knowledge in a safe space.”

Words: Melinda Halloran | Photography: Zoë Lonergan

As seen in Swell Issue 5.